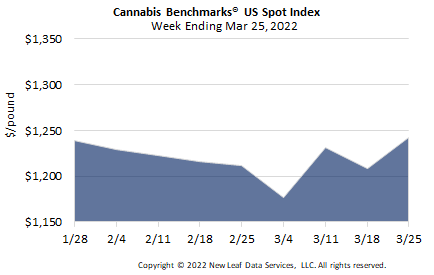

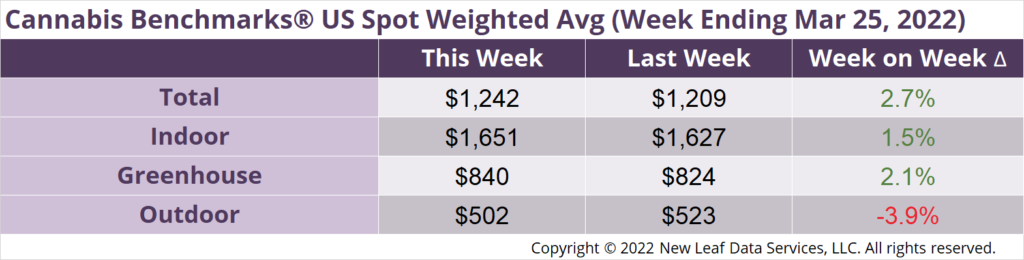

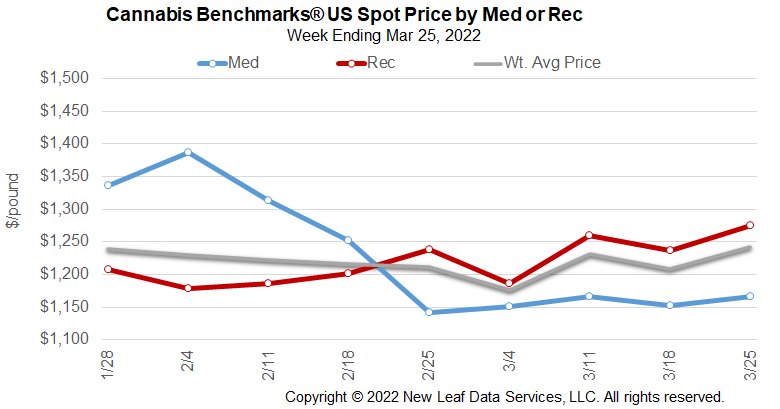

The U.S. Cannabis Spot Index increased 2.7% to $1,242 per pound.

The simple average (non-volume weighted) price increased $27 to $1,523 per pound, with 68% of transactions (one standard deviation) in the $684 to $2,362 per pound range. The average reported deal size declined to 2.4 pounds. In grams, the Spot price was $2.74 and the simple average price was $3.36.

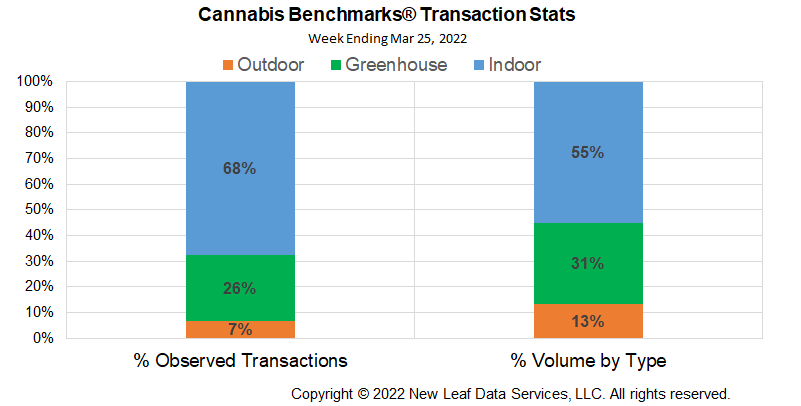

The relative frequency of transactions for indoor flower rose 3%, while greenhouse deal frequency fell 2% and outdoor deal frequency was unchanged.

The relative volume of indoor flower rose 2%; that of greenhouse flower fell 3%, while that of outdoor flower was unchanged.

Outdoor flower spot prices in legacy states – Colorado, California, Oregon, and Washington – are now within a $24 price range, from just below $500 to about $520 per pound, with the average price of outdoor product among legacy states sitting at about $506 per pound this week. Price convergence in these markets has picked up as pandemic demand has receded and supply has grown. There are economic reasons for price convergence and one of them is known as LOOP – the law of one price – which, as with other economic “laws,” sometimes works in real markets.

Growers around the country are often shocked at prices in states not their own. Californians are surprised that pounds of flower in Massachusetts are over $2,400, and were over $3,500 in November 2021, or that Illinois prices are over $3,400 per pound when their own product prices are sinking, despite being essentially the same product. Colorado and other western growers dream of selling into expensive East Coast markets one day, where pounds routinely go for $3,000 or more. Michigan growers are seeing prices fall on an almost daily basis, while prices in neighboring Illinois are nearly triple those in Michigan.

The theory or law of one price (LOOP) says different prices for the same commodity must converge via arbitrage. Buying cannabis in California and selling it in Illinois is arbitrage. All other elements being equal, if enough California cannabis ends up in Illinois, Illinois cannabis prices will fall toward those of California even as California prices rise on Illinois demand. Ultimately, the theory of one price and its resolution, arbitrage, collapse price differentials in efficient markets.

In the real world, federal cannabis prohibition denies the theory of one price, keeping price differentials in place by law, thus creating artificially segregated markets where the rules of economics and finance are denied by creating an unresolvable arbitrage. It is not that California cannabis does not end up in Illinois, it’s that current law prevents legal arbitrage, thereby denying the law of one price.

In the U.S., LOOP is thus defeated by federal law, which has erected what one might consider trade barriers. Trade barriers are, strictly speaking, rules put in place to protect one economy from another economy’s arbitrage attempts. Typically, trade barriers are between nations and, in the protected country, prevent “dumping” products on nations with nascent industries or economic inefficiencies that keep prices artificially high.

While not intentional, federal cannabis prohibition is a trade barrier, keeping prices higher in some states that may be lacking efficiency in production for various reasons. For example, California has the climate and experience to produce vast amounts of cannabis, while Illinois cannabis growing is constrained by multiple factors – including climate, rules against lower-cost outdoor cultivation, and an oligopoly on production – which keep prices artificially high. It is only through federal prohibition that enormous cannabis price differentials exist. Thus, when federal deregulation happens, arbitrage will take place and cannabis prices will find equilibrium.

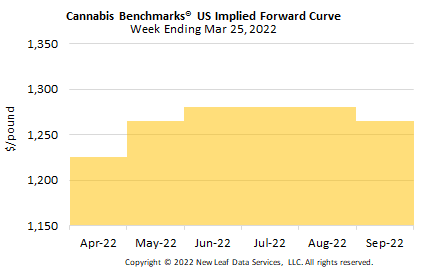

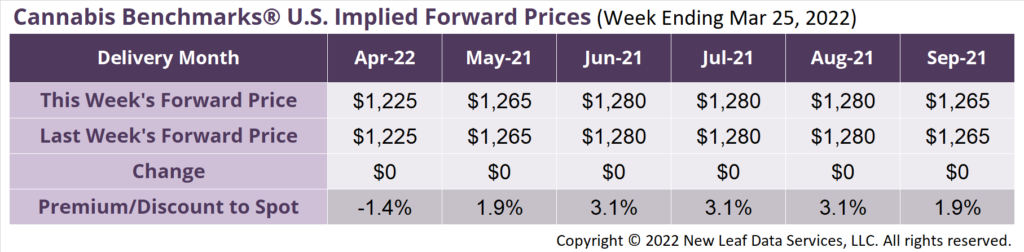

April 2022 Implied Forward closes unchanged at $1,225 per pound.

The average reported forward deal size increased to 79 pounds. The proportions of forward deals for outdoor, greenhouse, and indoor-grown flower were unchanged at 33%, 52%, and 15% of forward arrangements, respectively.

The average forward deal sizes for monthly delivery for outdoor, greenhouse, and indoor-grown flower were 94 pounds, 74 pounds, and 61 pounds, respectively.

At $1,225 per pound, the April 2022 Implied Forward represents a discount of 1.4% relative to the current U.S. Spot Price of $1,242 per pound. The premium or discount for each Forward price, relative to the U.S. Spot Index, is illustrated in the table below.

California

Interstate Commerce Bill May Draw Federal Fire

New Mexico

Eastern NM Retailer Has High Hopes for Adult Use Market

Illinois

Cannabis Licensing: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Massachusetts

Retail Ounce Prices Fall for 4th Month